How to Minimize Inheritance, Estate & Capital Gains Taxes

As we have discussed many times before, the two main goals of planning one’s estate are to ensure a smooth and meaningful transition (a legacy) and to maximize what you do pass on to the next generation. Below we’ll discuss that second goal: maximizing one’s estate by minimizing 3 potential tax hits that can dramatically lower how much you pass onto the next generation.

Before we can minimize taxes, we need to understand where they are coming from and why they’re being levied to begin with. As we are discussing inheritances and estate planning, there are three types of taxes we’re concerned about today: first, an inheritance tax; next, the dreaded estate tax (sometimes called the death tax); and, finally, capital gains taxes (meaning we’re crossing over with the investment world). Of course, there won’t be some bright line rule for everything. These taxes can apply federally, at the state level, both, or not at all. We will point out where these taxes come from, but you should always speak to a professional in your area for your specific situation.

Inheritance Taxes

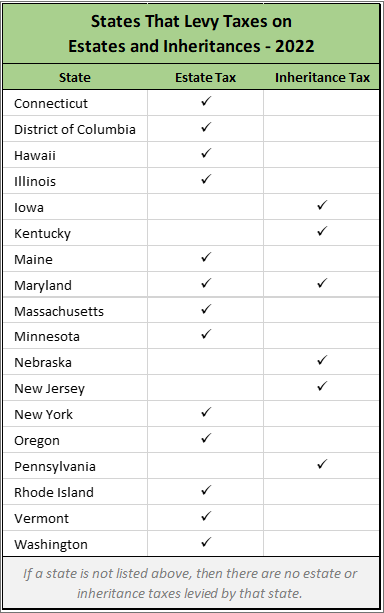

Let’s start with the first tax mentioned - the inheritance tax. This is, exactly what it sounds like, it’s a tax on the value of what one receives as an inheritance. There is no federal inheritance tax so we can disregard the feds for a moment. Even then, most states don’t levy an inheritance tax either. In fact, it’s only six states that levy inheritance taxes to begin with: Iowa, Kentucky, Maryland, Nebraska, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. If you’re in one of those states, then you should talk to an estate planning attorney near you to see if your heirs will qualify and whether you can take the steps below to minimize any potential taxes. Some states have a minimum threshold your estate needs to reach before taxes are imposed (such as a tax on anything over $1million for example) or there may be exemptions for certain individuals such as children or perhaps grandchildren. On top of this, the tax rate is going to vary as well, typically being on a sliding scale based on how much is subject to the tax. Think anywhere between 5% and 15% as an expected tax rate.

Estate Taxes

Next, let’s cover estate or death taxes. Estate taxes are something we have discussed a few times already, so we won’t jump into an exhaustive discussion on them here. To get to the point, estate taxes are a tax on the estate as a whole before it goes out to your heirs and is only imposed when the estate value is above a certain threshold. Unlike an inheritance tax, there is a federal estate tax that is equal to the lifetime gift tax exclusion level (which, as a bonus, is the amount of money you can give out during your lifetime before having to pay taxes on the amount gifted). Fortunately, this exemption level is $12.06 million for 2022, and will be $12.92 million for 2023. Additionally, these amounts are indexed to inflation, and thus will be adjusted each year (until 2026 depending on Congress). This means that no estate tax is due until the estate reaches above this $12million level and even then, is only levied on the amount of money above it. On top of this, there is even a process to use a spouse’s unused exclusion to increase your own exclusion level. You can read our post on portability HERE to learn more. However, once this tax kicks in, it’s a massive 40% tax rate.

Of course, there are a few states that want a piece of their estate tax pie - 13 to be exact: Connecticut, DC, Hawaii, Illinois, Maine, Maryland (double-dipping with their inheritance tax), Massachusetts, Minnesota, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Washington. Notably absent from this list is the blue-state-bastion of California. For those on the list, however, they are going to have different thresholds for when their estate tax kicks in - anywhere between $1million and over $7million. Additionally, just because you qualify or are excluded from the state estate tax, doesn’t mean the same will hold true for the federal estate tax, and vice versa. Again, speak to an attorney in your area if you think your estate might qualify for the estate tax.

Capital Gains Taxes

This brings us to capital gains taxes and our crossover with the investment world. Capital gains taxes are taxes on the gain in value of an asset when you finally sell it. If you bought a house for $200,000 and sold it for $500,000 30 years later, then a capital gains tax will be levied on that appreciation of $300,000 - the difference between what you acquired the property for and what you sold it for. However, what if you inherited the property? If you inherited the property, then your tax basis, or value you acquired the property for, will be considered the fair market value at the date of the original owner’s death and thus your date of inheritance. For example, your mom bought a house for $50,000. When she died and you inherited it, it was worth $400,000. You turn around and sell it for $425,000 a year later. Because you inherited the property, you received a stepped-up tax basis on the value meaning you're only paying capital gains on the $25,000 gain. The difference between the value at acquisition ($400,000) and what you sold it for ($425,000).

Thus, the tax minimizing strategy should be clear: if you plan on creating generational wealth and passing down appreciating assets such as real estate, then it is in your beneficiary’s best interest that they inherit the property, as opposed to being added onto title or being gifted the property outright. If they inherit the property, then they effectively inherit the appreciation it made during your lifetime.

As you can see, capital gains tax is yet another tax that can effectively shrink an inheritance if you don’t pay attention or minimize its impact. There is a federal capital gains tax on a sliding scale based on your income bracket, but the stepped-up tax basis concept I described will apply. In addition to this, many states levy their own capital gains taxes and have their own set of rules as to how it is calculated, what exclusions can apply due to an inheritance, and whether the state follows the IRS’s concept of a stepped-up tax basis like the one I just described. California, for example, does have a capital gains tax, but follows the same rules for a stepped-up tax basis on inherited property as the IRS, making planning around such easier with only one set of rules to consider. Again, each state will handle capital gains taxes differently.

How to Minimize These Taxes

Stepped-Up Tax Basis

Quick note before we jump into minimizing or eliminating these taxes - keep in mind that when I’m talking about property or assets, I don’t just mean real estate. Common assets included in estates are cash and other securities like stocks and bonds; retirement accounts like an IRA or 401(k); life insurance policies; collectibles or artwork; and, of course, real estate.

Now that we’ve covered the three types of taxes that can diminish your estate, let’s discuss what we can do to minimize or eliminate those taxes - some of which have already been hinted at. First, is the big one, ensuring your family or heirs can receive a stepped-up tax basis on any property they are due to inherit. Yes, it may seem easier to simply gift your house or investments to your children before you pass away - and they might even ask for it - but you would be doing them a disservice. Sometimes we have children that are wary of mom and dad going to an attorney who recommends using a trust because they think the attorney is locking away all their inheritance. However, once we discuss capital gains savings that can occur when they inherit assets as opposed to being gifted them, the smart children invariably turn around and tell mom and dad, “Yeah, you need to do this.”

Using a Living Trust

Next, we have the bread and butter of the estate planning world - the living trust. To start, as a bonus, a massive benefit of using a living trust means your estate can avoid going to probate court and go straight to beneficiaries, thus saving massively on court and attorney fees, on top of the privacy a trust brings, and faster timeline for distribution. Trusts are also how we can minimize or outright eliminate estate taxes though. How we do this is by creating trusts that allow for the splitting of an estate into various subtrusts - usually a Decedent’s and Survivor’s Trust for spouses - so that each portion of the estate can bring itself below the estate tax threshold.

For a simple example, let’s say we have a married couple whose estate is $24 million. When the first spouse dies, the estate is split equally between a Survivor’s A Trust and a Decedent’s B Trust. The A Trust continues as a typical revocable living trust for the surviving spouse, while the B Trust is irrevocable and cannot be changed. Let's say the federal estate tax level is $12 million even. You might think they are going to have to pay taxes on the difference between $12 million and $24 million. However, because these subtrusts were created, we are essentially creating two entities, each with their own tax returns, and thus each with their own shot at staying under the exemption level. Since the A and B sides are equal at $12 million each, both are now under the estate tax threshold, and thus neither subtrust owes estate taxes. We can take this a step further if there is more money in the whole estate, but that is a topic warranting its own discussion. For now, just remember that we can use trusts to minimize, if not outright avoid, estate taxes.

Utilize Alternate Valuation Dates

Another tool for minimizing inheritance and estate taxes is to check if an alternate valuation date on the estate will help. When it comes to taxes, you may figure estates (whether it be in a trust or through probate) are evaluated at the fair market value at the date of death. If so, you would be right, but only half right. Yes, we typically look at the date of death value, but we can use a different date’s valuation if we think it is going to be more tax-advantageous, and that is 6 months from the date of death. If an estate is taking over 6 months to gather and distribute - which can happen with trusts and is all but guaranteed in probate - and it appears as though the estate’s value has gone down over that time, then we are allowed to use the value as of 6 months from date of death for the value of the estate for tax purposes, thus decreasing the overall tax burden.

Roth Conversion

Next, we have retirement accounts, specifically, IRAs. Distributions from IRAs are taxable, except for Roth IRAs. While an inheriting spouse may be able to spread the distributions from an inherited IRA over their lifetime, other beneficiaries must take all their inherited IRA monies out within 10 years. They can do it all at once or over a period of time, but all funds must be distributed by the close of that 10-year window. This is where your financial adviser steps in. One method to minimize IRA taxes is by a Roth conversion. However, an adjustment like this is not something that should be taken lightly and will be dependent on your circumstances, so speak with your adviser before going full steam ahead.

Gifts and Charitable Giving

Lastly, we have gifts, whether they be gifts to others or charitable gifts. You are probably at least somewhat familiar with charitable gift giving. It’s where we donate, usually in the form of cash, to a charitable organization and are then allowed to write off said donation on our taxes, thus minimizing our normal taxes owed. Charitable giving is a tool often utilized in estate planning, particularly in the advanced estate planning world, when trying to navigate around various tax regulations while also contributing towards some social good or ideal.

Continuing with gifts and as briefly hinted at above, there is such a thing as a gift tax. A gift tax is a tax levied on the giver of the tax, not the recipient. Under federal law, you are allowed to give up to $16,000 per year to someone before a tax is owed. However, this $16,000 is tied to the recipient and everyone has their own gift tax exclusion limit, even among spouses. For example, I can give my son $16,000 this year and not pay a tax. On top of this, my wife can give him another $16,000, meaning he received $32,000 in total from mom and dad, and no gift tax is owed. Going further, I can give an additional $16,000 to my brother and still not have to pay a tax. We can do this every year so long as we live. However, there is also a lifetime gift tax exclusion equal to the federal estate tax exemption level (which remember is currently $12.06 million), meaning I can give away $12 million during my lifetime and still never pay a gift tax. Yes, this does create a potential capital gains tax issue, but gifting assets during one’s lifetime is a tool that some people use to minimize their potential estate tax exposure or a recipient’s potential inheritance tax exposure.

Note – The gift tax exemption level will be raised to $17,000 beginning in 2023. You can read our post HERE for more information.

Closing

At this point, we’ve covered a lot - from what potential taxes we are worried about in estate planning, to what assets are often included in estates and thus subject to taxes, before ending with many common techniques that can be utilized to minimize or avoid these taxes altogether. Just remember, no one estate is exactly like another, thus not every tool or strategy may be best for every estate. Always talk to a tax, legal or financial professional in your area before pushing full steam ahead.

BETHEL LAW CORPORATION

ESTATE PLANNING | ELDER LAW | BUSINESS PLANNING

CLICK HERE OR CALL US AT 909-307-6282 TO SCHEDULE A FREE CONSULTATION.